Why Fathers Matter in Early Childhood Development?

Research worldwide has shown that children thrive when both parents participate in early caregiving and learning. Father engagement is associated with stronger cognitive, language, and socio-emotional outcomes, including improved vocabulary, emotional regulation, and school readiness (Cabrera et al., 2018; Lamb, 2010; Sarkadi et al., 2008). The Lancet Early Childhood Development Series (2017) identified fathers as an “untapped resource” for nurturing care, while the Harvard Center on the Developing Child highlights that even small increases in responsive father–child interactions can produce lifelong benefits. In low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where caregiving norms often assign child-rearing primarily to mothers, engaging fathers represents both a challenge and a major opportunity. Fathers frequently hold decision-making power around children’s education, healthcare, and technology access (ICRW, 2020). Programs that succeed in involving them can therefore catalyse shifts not just in individual households, but across communities.

In India, this opportunity is particularly striking. According to NFHS-5 (2019–21), fewer than 20% of fathers engage daily in activities such as storytelling, reading, or playing with their under-five children. Yet national policies like NIPUN Bharat and Poshan Bhi Padhai Bhi increasingly call for “whole-family participation” in early learning. Bridging this gap requires evidence-based, father-inclusive strategies that are scalable, affordable, and context-sensitive.

For nearly a decade, Dost Education has worked with families and government systems across India to make early learning accessible, joyful, and rooted in everyday life through responsive caregiving. Through simple digital tools and community partnerships, Dost has supported thousands of caregivers to practice Talk, Care, and Play—the daily interactions that shape children’s earliest learning experiences. Its approach has been adopted in seven Indian states through partnerships with the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and other government departments.

Building on this experience, in July 2024, Dost with our research partner Purple Audacity Research and Innovation launched a six-month Tech + Touch Integrated Program Study in Uttarakhand. The study tests an integrated model combining accessible digital tools with light-touch community engagement to strengthen responsive caregiving among families, frontline workers, and local systems.

The program brought together three core initiatives:

The baseline, conducted with 380 households, offers rare insights into fathers’ roles and digital habits within low-income rural families.

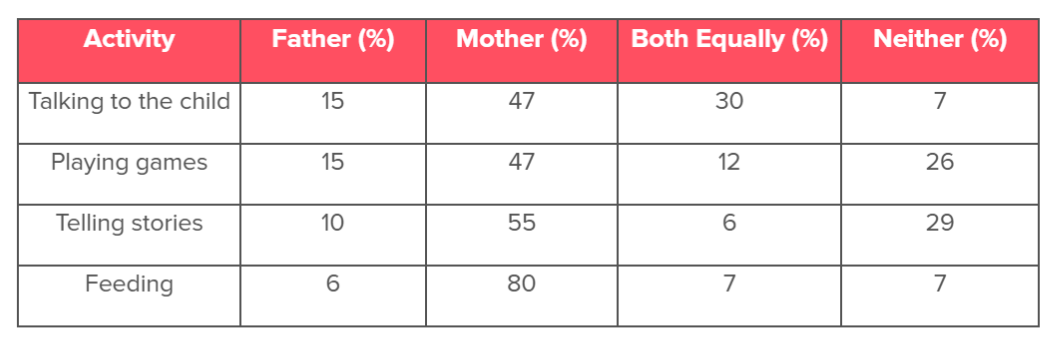

Yet shared caregiving remains limited: only 28% of parents reported that both parents equally support their child’s learning.

These findings echo broader national patterns and reveal a need for deliberate design that invites, not assumes, fathers’ participation.

Field observations from Dost’s community facilitators highlight several barriers that explain the gendered caregiving gap:

Despite these constraints, there is evident emotional openness. Fathers expressed a strong interest in supporting their child’s learning, provided that opportunities align with their time and comfort zones.

The study’s digital findings point to significant opportunities for low-cost father engagement:

By blending digital nudges with community reinforcement, Dost’s model lowers entry barriers for fathers who are time-poor but emotionally invested.

Dost’s “Champion Fathers” initiative identifies and celebrates men who model active caregiving in their communities. Their stories shared via digital channels and local meetings, serve as peer-led narratives that normalise father involvement. These champions often describe small but transformative acts: reading aloud before bedtime, playing during lunch breaks, or taking turns telling stories. As Irfan Ali, a 31-year-old father of Sidra, a 3.1-year-old, from Jaspur Rural block, puts it during a community meeting:

These moments are critical for cultural change. They reframe fatherhood as a nurturing identity, not just a providing one.

The baseline data from Uttarakhand offer three key takeaways for policy and programming:

As the program continues, forthcoming endline data will help test how these small shifts in perception translate into measurable behavioural change. The findings so far reinforce a simple truth: When fathers engage, children learn better, mothers feel supported, and communities become stronger. Engaging them is not just a gender strategy; it is a developmental imperative.

Dost Education is a nonprofit organisation based in India that designs scalable, low-cost digital and community-based programmes to promote responsive caregiving and early childhood development. Dost partners with governments and local systems to ensure every child gets a strong start through empowered families and inclusive learning environments.